Take half an hour and watch this.

The interesting thing about the debate is what’s missing. There’s no discussion about the purpose or meaning of Super League. There’s a large pile of cash on the table. The bigger clubs and RFL have plainly decided to accept this because they need the money more than anything else, and the deal supposedly comes with a ticking clock. That the RFL were reportedly prepared to accept the first offer without negotiating is extremely telling of the desperation involved.

On the other side, there’s the smaller clubs who feel owed something but are likely to be left in the cold or forced into shotgun marriages. Keighley had secured promotion and looked to be denied it by the creation of the Super League. Their insistence that their new grounds – capacity 10,000 – would set them up as a big club would be laughably small-minded if most Super League clubs didn’t operate along the same lines twenty-five years later. Featherstone Rovers, we are told, are the heart of a community ruined by industrial closures. Quite how such an economically disadvantaged community of 15,000 is meant to sustain a professional sports team in to the twenty-first century is not clear.

Instead, the RFL should have insisted that they needed more time to get stakeholders on board, develop a feasible structure for the sport and decide how to best invest the money. Off the cuff, all Maurice Lindsay can offer for the money’s ultimate destination is grassroots, developing the game and stadium upgrades with the influx of TV money – basically, following the Premier League’s lead a few years earlier – and it’s easy to see that being an enormous waste of money. Surely there isn’t a significant number of people who could be converted to rugby league, if only it were played in nicer stadiums.

Lindsay, however, was right that thirty-five does not go into fourteen. That there was ever an idea that that many fully professional clubs could be supported over such a small area is mystifying in retrospect. The intention, to merge existing clubs into new entities that would have a significant enough geographical and commercial reach to support a fully professional franchise, was sound in principle, as long as you didn’t look too much at details, like history, meaning and the defensive-borderline-paranoid psyche of the northern English.

The idea that a number of small English clubs with a hundred years of rivalry and basically nothing to show for it, would come together on an even footing to run a professional sports team is the kind of coked-up thinking that only the Super League war could throw up.

The mergers were dropped, Super League went ahead, the RFL got the money and not much else has changed for the English game in the next twenty years. The arrival of Canadian teams in 2017 and 2021 and a French club winning the Challenge Cup in 2018, signals the dawn of a new era – unplanned, unanticipated and somewhat unwelcome – that may well have been curtailed by the pandemic.

The golden opportunity provided by the virus to wipe the slate clean and begin anew has been wasted by the powers that be in both hemispheres. In all likelihood, the public bail-outs in England will only send more good money after bad and further entrench the status quo, not remove and replace it with something better. Defects in the game’s structure, writ large with the millions of dollars at stake and the attention of millions more, will remain, unaddressed.

In short, a Super League 2.0 is not coming.

Ironically, the renegotiation of the broadcast deal in Australia has only served to highlight how badly Super League 2.0 is needed. The executives at Nine can read the writing on the wall as well as the rest of us. The virus should have created a large socially isolated captive audience for television. Instead, it is accelerating the trends that were in place beforehand. People prefer to watch what’s available online, which is orders of magnitude better than free-to-air and the good stuff on pay TV can be pirated or streamed or VPNed for far less than Foxtel are asking. The economic uncertainty is resulting in slashed marketing budgets, meaning that even if anyone was watching TV, advertisers can’t afford the ad time anyway.

The acquisition of the Fairfax stable of newspapers in 2018 has only made the pressure worse. It remains to be seen if there’s a long term future for traditional mastheads in a digital age. Repeated slashing of quality and staff in the face of repeated poor corporate performance is eroding what’s left of the major dailies’ brands.

In either case, newspapers and free-to-air television are relics of an ecosystem that has been irreparably altered by the Chicxulub impactor that is the internet. The traditional media is on life support and, at the right price, rugby league is one of the machines that go ‘ping’.

* * * *

I’ve long been suspicious of Peter V’Landys.

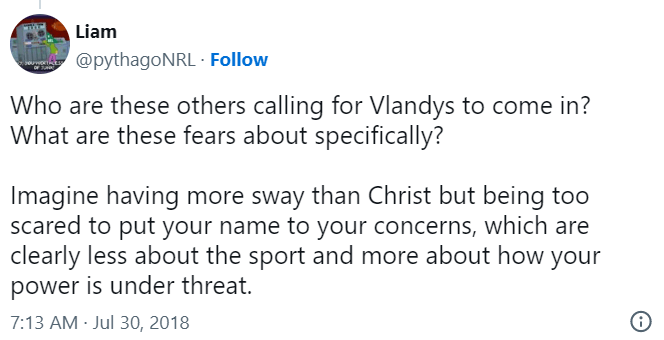

It wasn’t so much what V’Landys stood for because we didn’t know what that was in 2018. An unnamed someone decided to get the Andrew Webster to write and the Sydney Morning Herald to publish a puff piece and that rang alarm bells. The article was a hybrid of soft interview juxtaposed with “concerns”, which were unfounded and unattributed. It smacked of the same treatment lifelong deadshit politicians get before they challenge for the party leadership and become Prime Minister.

Journalists are meant to be smart, worldly and experienced but prove through their work that they do not deserve this reputation. You could argue that there is a higher game at play, and you’d be right, and that journalists are expected to walk a tight rope between speaking truth to power and maintaining access to the same power to do their jobs. But it seems here on the sidelines that the criticism of the powerful only ever comes when it serves the purpose of another power and almost never in the public interest.

Some have given up pretences entirely. Most would be better off re-positioning themselves as public relations officers for Newscorp or Nine and their interests and be done with it. It would at least be more honest and earn less public scorn.

It never ceases to amaze me how the media can whip up a frenzy apropos of nothing and, simply by whipping up the frenzy, make otherwise powerful and smart people do things that they’d rather not. It’s a damning indictment on the spinelessness of our leadership class that in the age of social media, the powerful aren’t able to completely bypass the traditional media, whose public trust is roughly on par with used car salesmen and real estate agents.

So it was, first with Peter Beattie and then later with Todd Greenberg. Beattie had stated that he hadn’t planned to be chairman of the ARLC for a long time but he obviously came in with a plan to shake things up quickly and decisively. He and Greenberg managed to get the international calendar to take some shape, had governments building new stadiums in Sydney to keep the grand final, had other governments paying for events like State of Origin and Magic Round, kicked off a profitable digital strategy and clubs and players were benefiting from a generous centralised grant and increased salary cap instituted by Beattie’s predecessor.

In short, they managed to make the NRL more reliant on itself and less reliant on the anonymous and not-so-anonymous bottom-feeders that have stifled the game’s progress for the last forty years lest it threaten their suburban fiefdom.

Then, in 2019, the drums started beating and like a self-fulfilling prophecy, Beattie had resigned and V’Landys ascended to the throne. Whether Beattie did not have the will to stave off the media’s inanity for another six months or simply had run out of political capital is not clear but it does seem like his work is unfinished. That Beattie’s legacy hasn’t been hugely tarnished by the same media suggests that he went quickly and willingly.

Once the chosen one had been crowned, he deigned to let us know what he stood for during his acceptance speech:

- Suburban stadium redevelopments in Sydney

- Tribalism, bringing it back

- Getting referees in line, maybe going back to one

- A nod to families

- Getting more out of gambling companies

- No mention of the international game or expansion

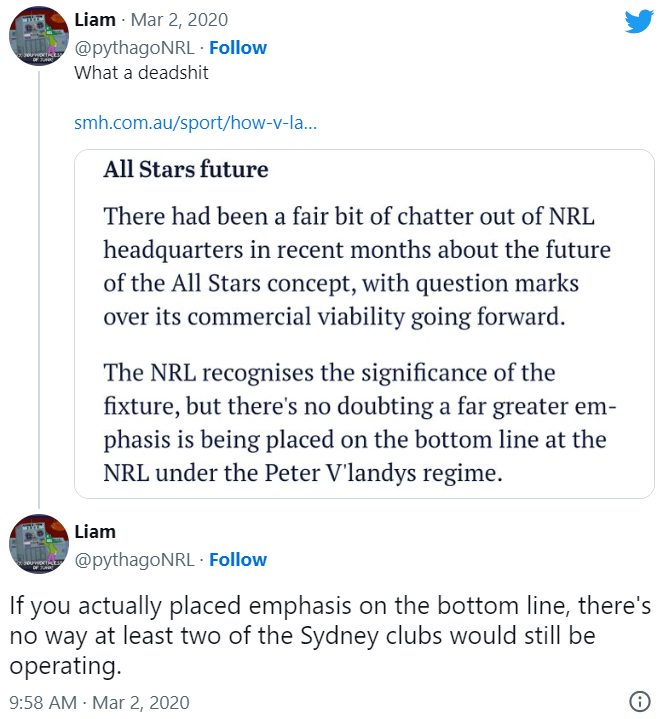

I’m not sure V’Landys even bothered to do a token reference to grassroots or bush footy. When pressed, we discovered that Brisbane still needed to be secured for rugby league, even though it has been played here since 1909, and that Western Australia was already a lost cause, a rusted-on AFL state. Much like the Melbourne Storm in Victoria, I guess.

The agenda strikes me as the perfect enapsulation of the Sydney boomer nostalgia bubble. I assume this is driven by faceless men behind the scenes, pining for a time when the footy was “better” and standing on a suburban hill with 2,000 other men was the pinnacle of the rugby league experience. With the passage of time, those who ache for the past forget the drawbacks but I suppose the authentic experience is regularly recreated at Leichhardt Oval. We are offerred the inferior product we know in lieu of a brighter but uncharted future.

Then, it was Greenberg’s turn. The knives were out and the cliches were flogged mercilessly. It was financial mismanagement supposedly. A huge head office and a white elephant digital strategy. Or maybe it was the response to the pandemic. Being reactionary? “Concerns” within clubland, possibly about the successful and necessary no-fault stand down.

Buzz Rothfield tried his best to gotcha and got absolutely banged in response.

https://twitter.com/thaidaynightfb/status/1246672725222903808

It didn’t matter.

Everyone stuck to their lines, which for the professional communicators among them were incredibly muddled. I was suffering from cognitive dissonance, that itchy feeling in your brain when you try to process contradictory information before you realise what’s wrong. It wasn’t true. It wasn’t even a shade of grey, it was clear cut. The game was profitable and growing. Everyone was getting paid. What the fuck was the actual problem? Am I really being gaslit by the rugby league media?

Even now, journalists, commentators and other people whose opinion we know only because they are paid to fill airtime and column inches, are unable to write or speak about Todd Greenberg’s legacy without referencing financial mismanagement. Traditionally, when one is accused of something like mismanagement, examples are proffered and yet, cursory glances at the facts reveal something completely different.

If something gets repeated often enough, it becomes true. The history books will record that head office costs were “bloated” and that he had to go.

We’re left to speculate what actually is going on because the people whose job it is to tell us won’t or can’t. Seemingly, the closest anyone came to the truth was that V’Landys doesn’t play nice, which is insanely childish.

Meanwhile, Peter V’Landys is treated with the same reverence as the second coming of Christ because apparently, the rugby league media’s main takeaway from watching world events of the last five years is that a strong man with a penchant for action, or at least being seen as imposing his will, and no respect for consultation is a good thing.

The current situation has placed existential pressure on the broadcasters. The NRL may be in breach of contract, even though suspending play is the right thing to do in the face of a deadly pandemic. This gives the broadcasters leverage to negotiate down a big expense in the form of NRL broadcast rights. The NRL doesn’t have enough ammunition to put up much of a fight and it seems that V’Landys isn’t interested in doing so. The broadcast deal has been (or maybe still is being?) extended for reduced value. It was then revealed that Nine, not so much as hating the digital strategy, actually coveted it.

V’Landys sits at the nexus of a major power play, from clubs and broadcasters threatened by a brave new world that might get by without them. I don’t claim a conspiracy because its laughable these people could have planned anything two years in advance. The irony is that if the clubs could be trusted to cooperate like this, they could form a cartel to protect themselves and we might actually be better for it.

Quite who did what and what the ends are still isn’t clear. I’d speculate that V’Landys is treated as the messiah because he will lead the game back in time to a golden age that only exists in the mind of some powerbrokers. It could be the much more likely and grubbier alternative that people who take big dollars out of the game want to continue to take big dollars out of the game. Or both.

The full picture will be drip fed through selected journalists over time and we will see it when it will be too late to do anything meaningful about it, if we could even do anything about it now.

Rugby began as a means to turn schoolboys into men. Rugby and the Muscular Christian ideology mirrored each other in the mid-to-late 19th century. When the Northern Union went its own way in 1895 and the Rugby Football Union another, the RFU doubled down on its elitism, deliberately avoiding the mass spectacle and the associated rougher element, creating a game to instil the same moral education that a boy would receive at Eton.

The idea that the private schooling system can produce moral individuals is laughable. Take a quick glance at the leadership class’ performance, from Gallipoli to Brexit, and report back on the results. The rich are always happy to sacrifice the poor to protect the rich and hate them for reminding them that their wealth is often unjust.

If you needed further evidence of rugby-as-morality’s failings, the collaboration between rugby union and the Nazi-aligned Vichy government in France during World War II and tours to apartheid South Africa in the 1980s should seal the deal.

After 1895, rugby league needed to appeal to the masses. Professional sport has to be entertaining to get people through the gate and, later, to turn on the TV. Its working class roots in the northern industrial towns of England and the suburbs and regional areas of New South Wales, Queensland and Auckland imbued a sense of meritocracy. It doesn’t matter who you are, just how well you can play.

As a result, rugby league clubs and leagues tend to be more inclusive and representative than the prevailing cultural mainstream. If you’re reading this, you will probably be able to rattle off a litanical list of milestones. That’s not to say league hasn’t had its moments. The reception of Olsen Filipaina and other Polynesians to Sydney rugby league and the naming of the Edwin Brown grandstand in Toowoomba strike me as two particularly gross examples. Still, it’s clear the culture of league is usually better than the culture around it.

Once the virus is over, fees for broadcast rights will remain critically important for both rugby codes. That union was a generally unappealing game did not matter for most of its history. If you don’t pay your players, then there’s no need to chase broadcast dollars by tidying up your product. Once professionalism was officially legalised in 1995, and it was clear that the world had moved beyond union’s notions of how society should operate, union became subject to the same market forces as league. The result is that union is following league’s evolutionary path to keep the ball in play for as long as possible, minimising scrums and technical penalties. It would not surprise me to discover that they are considering abolishing the lineout, dropping two players from each side and a means to limit possession.

As the two codes converge, already very similar to the uninitiated and now subject to the same selective pressures, we start to wonder what rugby league, the somewhat smaller and significantly less powerful of the two codes, will do to make its mark in the world. If people don’t know the whole story, then there is little hope for league’s long term survival. Moreover, in a globalised, kleptocratic, winner-takes-all economic system, we don’t know whether rugby will be able to find breathing room in the face of North America’s big four and European soccer becoming world-spanning sporting behemoths.

On rugby’s new frontiers, people will tell you both codes of rugby get along and there’s no code wars. The same people will contribute “why can’t we all just get along?” to the political discourse, seemingly unaware that some are campaigning for their very lives in the face of prejudice, inequality and fascism. It is the same attitude but, it should go without saying, the stakes are many orders of magnitude less significant in sports than politics.

Still, if there were no stakes, then the rugby codes would merge and we could get on with working out how to co-exist with other sports. That will never happen because there are stakes and wounds and history that have not been resolved. It is not an irrational take that union is the embodiment of late 19th century aristocracy, elitist and exploitative, cosy with fascism and league should never reconcile with that world view. The irrational take is that these things don’t matter, they’re in the past and you’re being childish by having feelings about them.

You might wonder why I’ve bothered to tell you these stories and what brings together these disparate thoughts. Over the off-season, I wrote approximately this same piece but it was lengthier, unedited and all-around insane. It will remain unpublished.

But there’s a lot of Big Stuff happening right now. It helps to talk about it and helps fill the time until rugby league’s imminent return. It’s also interesting to me at least to consider how the past and the present might inform the future.